For Joan Didion, a clear-eyed love letter

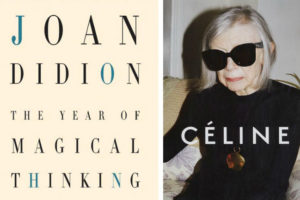

Joan Didion had a glittering journalistic success with Slouching Towards Jersualem in the early 1970s. But she really cemented her position as a writer with The Year of Magical Thinking, a mature, heart-wringing remembrance of her husband and daughter. Now, her nephew has created a documentary tribute.

About a third of the way through The Center Will Not Hold, Griffin Dunne’s intimate, affectionate, and partial portrait of his aunt Joan Didion, which premières on Netflix this week, a riveting moment occurs.

Dunne, an actor, producer, and director—and the son of Didion’s brother-in-law, the late Dominick Dunne—is questioning Didion about Slouching Towards Bethlehem, her essay describing the hippie scene of Haight-Ashbury in 1967.

That essay consisted of a fragmentary rendering of a dysfunctional social world that had been improvised by vulnerable children and predatory grownups, framed by Didion’s elegiac, magisterial summation of a civilization gone off its rails: “Adolescents drifted from city to torn city, sloughing off both the past and the future as snakes shed their skins, children who were never taught and would never now learn the games that had held the society together.”

It was the work for which Didion was best known and most esteemed in the many decades of literary production that preceded The Year of Magical Thinking, the memoir of marriage and bereavement that, when it was published, in 2005, granted her a vast, popular success.

In one of several genial interviews, Dunne asks Didion about an indelible scene toward the end of her Haight-Ashbury essay—which, as any student who has ever taken a course in literary nonfiction knows, culminates with the writer’s encounter with a five-year-old girl, Susan, whose mother has given her LSD.

Didion finds Susan sitting on a living-room floor, reading a comic book and dressed in a peacoat. “She keeps licking her lips in concentration and the only off thing about her is that she’s wearing white lipstick,” Didion writes.

Dunne asks Didion what it was like, as a journalist, to be faced with a small child who was tripping. Didion, who is sitting on the couch in her living room, dressed in a gray cashmere sweater with a fine gold chain around her neck and fine gold hair framing her face, begins. “Well, it was . . .” She pauses, casts her eyes down, thinking, blinking, and a viewer mentally answers the question on her behalf: Well, it was appalling. I wanted to call an ambulance. I wanted to call the police. I wanted to help. I wanted to weep. I wanted to get the hell out of there and get home to my own two-year-old daughter, and protect her from the present and the future.

After seven long seconds, Didion raises her chin and meets Dunne’s eye. “Let me tell you, it was gold,” she says. The ghost of a smile creeps across her face, and her eyes gleam. “You live for moments like that, if you’re doing a piece. Good or bad.”

This, too, is gold, as Dunne recognises. (No doubt Didion, who seems never to have faltered in the command of her own image-making, recognises it, too.)

The exchange shows Didion offering a distillation of her art, and shows her mastery of the journalist’s necessary mental and emotional bifurcation.

To be a reporter requires a perpetual straddle between empathy and detachment, and Didion’s refinement of that capacity is part of what has long made her a role model—to use that unfortunate but necessary phrase—especially to female writers of slight build, neurasthenic temperament, and literary aspiration.

Without empathy, it would be impossible to persuade a skeptical, sometimes strung-out member of the counterculture to lead you to your quarry. (In the essay, Didion makes it clear that she has specifically sought in her reporting to find hippiedom’s youngest enrollees.)

Full story: The Most Revealing Moment in the New Joan Didion Documentary (The New Yorker)

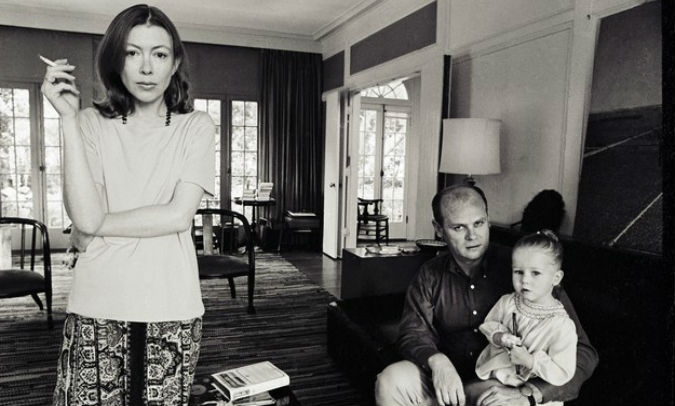

Main image: Joan Didion pictured with John Gregory Dunne, who died in 2003, and their daughter, Quintana Roo Dunne, who died a year and a half later.Photograph by Julian Wasser/Netflix