Federer’s form: An impossible role model?

More than 14 years after he first became No. 1, Switzerland’s Roger Federer has just returned to the top of the ATP Rankings for a historic fourth stint at the pinnacle of men’s professional tennis. Federer, who began his 302nd week at No. 1 on 29 October 2012, breaks a number of ATP Rankings records by replacing his great rival, Spain’s Rafael Nadal, in top spot.

Just 13 months ago, Federer returned from a knee injury at No. 17 in the ATP Rankings and has since compiled a 64-5 match record — including nine titles from 10 finals — in that period. Today, he now holds records for the longest period between stints at No. 1, as the oldest player to attain top spot and for the longest duration between first and last days at the summit of men’s professional tennis.

Last year, when Federer was on his way back to Number 1, Louisa Thomas filed this story for The New Yorker.

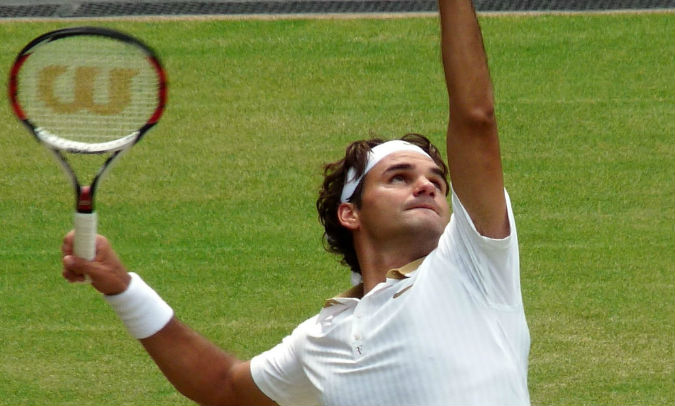

A few minutes after I arrived at Wimbledon, walking through the grounds, I felt a flutter in the air, a quickening. Heads were turning, looking up. A murmur rippled through the throng, and then a cry: “Roger!” I looked up. Roger Federer was crossing the bridge connecting Centre Court with the players’ area, trim in a navy polo. He paused at the shouts and looked down. The crowd below was at a standstill, necks craning, phones out to record the moment. He raised his hand in a wave, acknowledging his adoring subjects. The shouting turned to a roar. I—who have never had trouble cheering for his rivals—felt the silent cry in my own heart. Long live the King!

Roger Federer won a tennis tournament today. Perhaps you’ve heard: Wimbledon, his eighth. His nineteenth Grand Slam title. The final match, a 6–3, 6–1, 6–4 victory over Marin Cilic, was entirely forgettable. Cilic showed only flashes of the impressive serving, aggressive baseline play, and quick reflexes that brought him this far. After the first few games, Federer was never tested. It was unlike the tense and brilliant match that Cilic and Federer played in the semifinals at the 2014 U.S. Open, or the tight contest between the two in the quarter-finals of Wimbledon last year, when Cilic held match points but Federer went on to win. There was only one memorable moment this time, when Cilic was down a set and a break and began to cry. He was struggling with a bad blister on his foot, and with the moment. “It was just that feeling that I wasn’t able to give the best,” he later explained. He sat in his chair during the changeover, surrounded by the physician and trainer, and sobbed.

Tennis is a game that tortures souls. It is the loneliest sport, a contest not only of player against opponent but mind against body, mind against self. Everything about it is brutal, on and off the court: the pace and the weight of the ball, the pressure, the travel, the redundancy, the expectations, the carping press. It is not uncommon for players—including many of the greatest champions—to show their nerves and their temper during a bad patch, to crack.

Federer is different. Yes, he was once a kid with frosted hair and a habit of wrecking racquets. (The first time his wife, Mirka, saw him, he once recounted, he was on the court in Switzerland screaming and smashing his stick. As he told the Guardian, his voice adopting a mocking tone, “she was like . . . ‘Yeah! Great player, he seems really good! What’s wrong with this guy?’ ”) But he long ago became the paragon—even a parody—of gentility, calm and regal.

It can be hard to see past the legend, even on the court, if only because his play is so beautiful. Whether you’re religious or not, watching him is an aesthetic experience. I realized that I had lost whatever credibility I had as an analyst of his game, if I ever had any, during the 2015 U.S. Open, when he hit a squash shot instead of running two feet to his right to hit a routine forehand. It was a lazy shot, but, as his racquet scythed the air, I thought it was the most gorgeous thing I had ever seen.

Still, what he has done in the past six months, since taking the second half of last year to recover from a knee injury and to give his aging body time to refresh, is amazing by any measure. At the age of almost thirty-six, he has kept improving. He has changed his backhand, driving it more emphatically; he’s recalibrated the balance between his net and baseline play; he’s hit serves with perfect accuracy. He has used his preternatural timing and reflexes to unsettle the game of grinders, shot-making his way to win after win.

“I’ve never felt more pressure playing against another player as I did against Roger when he’s on, where you feel like you have no room to breathe,” Tommy Haas, who is thirty-nine, told me at Indian Wells in March, which Federer went on to win. (Haas, as it happens, became the last man to beat Federer, when he did it in Stuttgart in June.) “You’re on your toes. You don’t know—is the ball going there? Is it going here? And the court is so big. You can play really good tennis, and you feel like you have chances, but you lose 6–4, 6–4, you’re not close.”

Against Cilic, Federer played a startlingly clean match. He won eighty-one per cent of his first serves and seventy-one per cent of his second ones, and had twenty-three winners to only eight unforced errors. An underrated returner, he also easily handled Cilic’s big serve. Federer won Wimbledon, his second major of the year, without dropping a set.

When it was over, he sat in his chair and also cried. The title meant a lot to him, you could tell. Still, the victories are not the most extraordinary thing about Federer to me these days. Winning seems like a natural consequence of a more general joy…

Full story The General Joy of Roger Federer, Wimbledon Champion Once Again in The New Yorker.